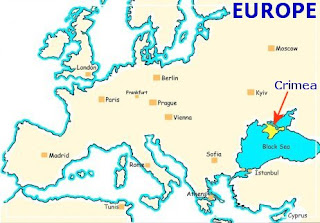

• Factors leading to possible conflicts are increasing in Crimea, raising the question of whether Crimea will be the next flashpoint in Europe’s neighbourhood.

• Unresolved economic problems and bad governance are giving rise to conflicts between the Slav and Tatar

populations of Crimea.

• Ukraine’s central government has less influence than Russia in Crimea, feeding grounds for contestation of Ukraine’s sovereignty over the peninsula.

• The EU must develop a long-term conflict prevention strategy based on dialogue, aid, investments and prospective Ukrainian accession.

The Russia-Georgia war over South Ossetia and Abkhazia in August 2008 has provoked debate over the need for a more active EU engagement regarding conflict prevention in the Eastern neighbourhood. Voices in the East and West have drawn scenarios for similar tensions in Crimea in Ukraine.

THE CHALLENGE

Although Ukraine is recognised as stable in contrast with its neighbours, a number of factors indicate that Crimea could be the next flashpoint in Europe’s neighbourhood. Internally, the territory suffers poor and corrupt governance, unresolved economic and social problems and increased tensions in relations between the Slavic majority and the Tatar minority. Externally, Russia is expanding its influence in the region. There is an ethnically Russian majority and the Russian fleet is stationed at Sevastopol harbour. This contrasts with Kyiv’s ineffective governance of the region and tensions between the Ukrainian and Crimean authorities which exacerbate the situation. Instruments of long term conflict prevention have not been directed at Crimea. Neither the United States nor the EU has specifically targeted Crimea with its aid programmes. The UNDP programme in Crimea is the most important of the few exceptions. This “Crimea Integration and Development Programme”, financed by a pool of government donors including Canada, Norway, Switzerland and Sweden (as the only EU member), focuses on areas such as democratic governance, economic development in rural areas, tolerance through education and human security monitoring. Another UNDP programme, which has been supported by the EU since 2008, is aimed at promoting local development through community mobilisation. Some new EU member states (Poland, the Czech Republic) and private donors (the Soros Foundation) pay some attention to civil society support in Crimea within their country programmes for Ukraine. Crimea is not targeted in the political dialogue between Ukraine and the EU. The European Neighbourhood Policy Action Plan between Ukraine and the EU only touches upon regional development and the continuation of administrative and local government reforms. The implementation of these commitments is poor, however. The OSCE and the Council of Europe focus on Crimea only through the prism of minority rights protection. Due to the 2008 war between Georgia and Russia, as well as internal political tensions in Ukraine, Western democracies are revisiting their policies on conflict prevention in Europe’s neighbourhood. The Americans have also started to improve their image through investment promotion and social projects after the anti-NATO and anti-American protests in Feodosia in 2006. Nevertheless, the idea of opening a US Consulate in Crimea has met with resistance from the Crimean Parliament. Following a similar path, several EU member states and the European Commission recently came up with a proposal for a Joint Cooperation Initiative in Crimea. Its objective is to mobilise resources for the development of Crimea while raising the EU’s profile in the region. The EU aims at harmonising bilateral and Community assistance with a clear division of labour. Participating EU member states will be responsible for a given priority sector (e.g. environment, civil society, economic development etc.).

The central role in the implementation will be given to the UNDP. So far, mainly northern EU members (Finland, Sweden, the Netherlands, the UK), Germany and several new member states (Poland, Hungary, Lithuania) have adhered to the initiative. No similar effort is being made within the recently launched Eastern Partnership, however. While a Czech proposal called for the Eastern Partnership to focus on the frozen conflicts, little of substance was included. The Commission limited its offer to dealing with the conflicts through better integration of the Eastern neighbours into the Common Foreign and Security Policy and the European Security and Defence Policy, as well as setting up an early warning mechanism, cooperation on arms exports and involving civil society organisations in confidence building in areas of protracted conflict.

FRATERNITY VERSUS FRAGILITY

Crimea is the most distinct and complicated region of Ukraine due to its history, ethnic composition, cultural legacy and constitutional status. It is the only Ukrainian region where Russians form the major ethnic group representing 58 per cent of the population, followed by 24 per cent of ethnic Ukrainians, and 12 per cent of Crimean Tatars who had been forcibly expelled to Central Asia by Stalin in 1940s and began to return since the early 1990s. Belarusians, Armenians, Jews, Azeris, Greeks, Bulgarians, Germans (together around 5 per cent) add further diversity. Crimea is granted political autonomy by the Constitution of Ukraine and this status is confirmed in the Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (hereafter the ARC). It is the only region of Ukraine which has such an arrangement. Crimea has its own parliament, which appoints and designates a prime minister with the consent of the President of Ukraine.

The most spoken language is Russian, which the Crimean Constitution grants official status. In fact, Russian is the sole language used in the public administration, the media and the educational system in Crimea. Although Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar have the same status, these are rarely used. A reality check confirms this: while there are 987 Russian-language printed media in Crimea, there are only five published in Ukrainian and four in Crimean Tatar. Despite the 250-thousand strong Crimean Tatar population, there is not a single Tatar school. Even though Crimea voted in favour of Ukrainian independence in the 1991 referendum, the early 1990s saw the rise of separatist movements. When the Crimean government introduced the post of President of Crimea, the elected pro-Russian politician Yuriy Meshkov disbanded the Crimean Parliament and called for independence. Separatism flourished as Russia was reluctant to recognise Ukraine’s sovereignty over the peninsula. only the adoption of the Constitution of Ukraine in 1996 and the ratification of the Ukraine-Russia Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership in 1997 (tied to the agreements arranging the status of the Russian Black Sea Fleet until 2017) led to an easing off of territorial tensions. Loyalty to Russia among Crimeans is still strong and this has increased during the last few years. According to a recent study by the Razumkov Centre, a Kyiv-based think-tank, 32 per cent of Crimeans do not consider Ukraine as their native country, while 48 per cent would like to change their citizenship, mostly to Russian. Importantly, 63 per cent of the population would support the idea of Crimea joining Russia.However, there is no single vision on the future of the region – the same proportion would support greater Crimean autonomy within Ukraine. Only 25 per cent are in favour of Ukraine joining the European Union, with 52 per cent against; in Ukraine as a whole, support for EU integration (47 per cent) prevails over opposition to it (35 per cent). Tensions have deepened over land, political, social, economic and language rights, over historic and religious places, and between Kyiv and local authorities. Often the division lines lie between the Russian-Slav and the Crimean Tatar populations. These are exacerbated by the hate speeches of the Crimean media against the Tatars and the Muslim population. Ukrainian authorities have not developed legislation that would renew Crimean Tatar rights as an aboriginal ethnic group. This has pushed the Tatars towards radical behaviour, such as illegal land grabs, street protests and the radicalisation of national movements. Land is one of the major sources of conflict. The land promised to the repatriated Tatars is also a major focus of corruption in which local and national authorities and the Tatar representatives are involved.

INFLUENCE VERSUS GOVERNANCE

When the post-Orange Revolution leadership of Ukraine took a more decisive stance towards EU and NATO integration, Russia, through both its increasingly aggressive rhetoric towards Ukraine and boosted funding for the Russian community of Crimea, signalled that it was willing to use Crimea as a bargaining chip vis-àvis Ukraine. Moscow’s claims toward Crimea have become more frequent, culminating in the Russian State Duma’s decision to seek the abrogation of the 1997 Treaty if Ukraine joined the Membership Action Plan for NATO or forced NATO accession. Additionally, the Russian media have created an image of Ukraine as a country that discriminates against the Russian-speaking population.

The Russian position is backed by the influence it has over the Crimean peninsula, which is stronger than that of Ukraine. A constant source of tension in Ukraine-Russia relations, the Russian Black Sea fleet is also a main source of income for the Sevastopol budget and inhabitants. Russia is the largest investor in the region and the main destination of Crimean exports – although overall Crimean exports to the EU almost equal those to Russia. The dominance of the Russian media and the power of pro-Russian political parties is crucial. The Russian Community of Crimea (RCC), an NGO funded by the Moscow major Yuriy Luzhkov’s “Moscow – Crimea” Foundation, together with the Russian Block, has a 30 per cent quota in the Block for Yanukovych, which has formed an 80-seat ruling coalition together with other pro-Russian parties in the 100-seat Crimean Parliament. Moreover, the RCC’s head, who holds the chair of the Crimean parliament’s deputy speaker, is a member of the Compatriots’ Councils for the Moscow government and the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Although Crimea is an issue in Ukraine, Kyiv has no Crimea policy. As some European diplomats cautiously note, the political establishment in Kyiv cannot – and perhaps does not want to – make serious efforts to integrate Crimea fully into Ukraine’s political and social context. Rather, it is merely interested in keeping the current status quo. Indeed, Kyiv lacks the necessary resources, and the political elite remains inward looking. The national government fails to implement even the adopted policy decisions regarding Crimea. Local Crimean authorities feel unheard and ignored by the Kyiv government as political dialogue is limited to the party structures’ communications during the electoral campaigns. No wonder there is often harsh Crimean resistance following decisions by Kyiv, as happened after the decision of the Minister of Education to introduce school graduation tests only in Ukrainian. In critical situations the Crimean politicians and population reveal more public support for the Russian authorities than those of Ukraine.

Despite the favorite local habit of waving Russian flags (although the Crimean, very similar to the Russian, is much more popular) and protesting on every possible occasion against NATO, most experts agree that there is a reasonably strong Crimean identity among locals – Russians and Tatars both. Moreover, Crimean politicians certainly feel that the depth of the autonomy ensured by the weakness of the Ukrainian government gives them a stronger position than the authoritative Russia ever would.

Last, but not least, Kyiv tends to forget its biggest leverage toward Crimea – its European integration plans. With more Western (especially European) engagement, Crimea could even be an engine of integration, as socio-economically it would probably benefit the more from this than other regions. This dimension could in fact capitalise on the growing interest in Crimea’s development expressed by the EU.

THE EU AS NEWCOMER

By facilitating social and economic development, promoting good governance, access to citizens’ rights and democratic dialogue, and increasing the demand for European integration, the EU would help avert the roots of internal conflicts. Despite the geopolitically oriented rhetoric, local partners nurturing the status quo are ready to cooperate, especially as the EU is a more credible partner for Crimea’s society and authorities in contrast with the U.S. This would be the EU’s long term investment not only in projecting stability in Crimea, but in the whole Eastern Neighbourhood.

Within the political dialogue with Ukraine, the EU should press the Kyiv government to continue with decentralisation and local and regional government reforms, focusing on economic development (based on the wasted potential of Crimea in trade, tourism, etc.), as well as introducing effective multi-ethnic management that might encompass all the key ethnic groups living in Ukraine today.

At the regional level, apart from the economic and social development of Crimea, the EU should aim at promoting socialisation and better communication in a Crimea-Ukraine-EU triangle through the following policies: educational mobility both to the EU and within Ukraine of Crimean students and teaching staff; joint EUCrimea university programmes in such areas as tourism; mobility programmes for journalists

and local government representatives; European-Crimean twin towns programmes; and trilateral (EU-Ukraine-Crimea) and bilateral (EUCrimea, Ukraine-Crimea) civil society cooperation in areas of human rights, good governance, multicultural and multi-ethnic management and community services.

European-Crimean cultural communications should be facilitated. EU member states’ institutions should launch their activities in Crimea. People-to-people contacts would benefit from the development of low-cost international air and sea transport communications. The EU countries’ consular networks should be spread to Crimea to support trade, cultural activities, people-to-people contacts and a better understanding of the region. None of the EU member states has its consulate in Crimea. Lithuania, Estonia and Hungary have honorary consulates, while the closest consulates are those of Poland, Romania, Greece and Bulgaria, in Odessa. Internationally, the EU should make better use of the opportunities for regional cooperation opened up by the Black Sea Synergy and the Eastern Partnership and seek for the promotion of EU-Ukraine-Russia and EU-Ukraine-Russia-Turkey cooperation aimed at the development and European integration of Crimea.

• Unresolved economic problems and bad governance are giving rise to conflicts between the Slav and Tatar

populations of Crimea.

• Ukraine’s central government has less influence than Russia in Crimea, feeding grounds for contestation of Ukraine’s sovereignty over the peninsula.

• The EU must develop a long-term conflict prevention strategy based on dialogue, aid, investments and prospective Ukrainian accession.

The Russia-Georgia war over South Ossetia and Abkhazia in August 2008 has provoked debate over the need for a more active EU engagement regarding conflict prevention in the Eastern neighbourhood. Voices in the East and West have drawn scenarios for similar tensions in Crimea in Ukraine.

THE CHALLENGE

Although Ukraine is recognised as stable in contrast with its neighbours, a number of factors indicate that Crimea could be the next flashpoint in Europe’s neighbourhood. Internally, the territory suffers poor and corrupt governance, unresolved economic and social problems and increased tensions in relations between the Slavic majority and the Tatar minority. Externally, Russia is expanding its influence in the region. There is an ethnically Russian majority and the Russian fleet is stationed at Sevastopol harbour. This contrasts with Kyiv’s ineffective governance of the region and tensions between the Ukrainian and Crimean authorities which exacerbate the situation. Instruments of long term conflict prevention have not been directed at Crimea. Neither the United States nor the EU has specifically targeted Crimea with its aid programmes. The UNDP programme in Crimea is the most important of the few exceptions. This “Crimea Integration and Development Programme”, financed by a pool of government donors including Canada, Norway, Switzerland and Sweden (as the only EU member), focuses on areas such as democratic governance, economic development in rural areas, tolerance through education and human security monitoring. Another UNDP programme, which has been supported by the EU since 2008, is aimed at promoting local development through community mobilisation. Some new EU member states (Poland, the Czech Republic) and private donors (the Soros Foundation) pay some attention to civil society support in Crimea within their country programmes for Ukraine. Crimea is not targeted in the political dialogue between Ukraine and the EU. The European Neighbourhood Policy Action Plan between Ukraine and the EU only touches upon regional development and the continuation of administrative and local government reforms. The implementation of these commitments is poor, however. The OSCE and the Council of Europe focus on Crimea only through the prism of minority rights protection. Due to the 2008 war between Georgia and Russia, as well as internal political tensions in Ukraine, Western democracies are revisiting their policies on conflict prevention in Europe’s neighbourhood. The Americans have also started to improve their image through investment promotion and social projects after the anti-NATO and anti-American protests in Feodosia in 2006. Nevertheless, the idea of opening a US Consulate in Crimea has met with resistance from the Crimean Parliament. Following a similar path, several EU member states and the European Commission recently came up with a proposal for a Joint Cooperation Initiative in Crimea. Its objective is to mobilise resources for the development of Crimea while raising the EU’s profile in the region. The EU aims at harmonising bilateral and Community assistance with a clear division of labour. Participating EU member states will be responsible for a given priority sector (e.g. environment, civil society, economic development etc.).

The central role in the implementation will be given to the UNDP. So far, mainly northern EU members (Finland, Sweden, the Netherlands, the UK), Germany and several new member states (Poland, Hungary, Lithuania) have adhered to the initiative. No similar effort is being made within the recently launched Eastern Partnership, however. While a Czech proposal called for the Eastern Partnership to focus on the frozen conflicts, little of substance was included. The Commission limited its offer to dealing with the conflicts through better integration of the Eastern neighbours into the Common Foreign and Security Policy and the European Security and Defence Policy, as well as setting up an early warning mechanism, cooperation on arms exports and involving civil society organisations in confidence building in areas of protracted conflict.

FRATERNITY VERSUS FRAGILITY

Crimea is the most distinct and complicated region of Ukraine due to its history, ethnic composition, cultural legacy and constitutional status. It is the only Ukrainian region where Russians form the major ethnic group representing 58 per cent of the population, followed by 24 per cent of ethnic Ukrainians, and 12 per cent of Crimean Tatars who had been forcibly expelled to Central Asia by Stalin in 1940s and began to return since the early 1990s. Belarusians, Armenians, Jews, Azeris, Greeks, Bulgarians, Germans (together around 5 per cent) add further diversity. Crimea is granted political autonomy by the Constitution of Ukraine and this status is confirmed in the Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (hereafter the ARC). It is the only region of Ukraine which has such an arrangement. Crimea has its own parliament, which appoints and designates a prime minister with the consent of the President of Ukraine.

The most spoken language is Russian, which the Crimean Constitution grants official status. In fact, Russian is the sole language used in the public administration, the media and the educational system in Crimea. Although Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar have the same status, these are rarely used. A reality check confirms this: while there are 987 Russian-language printed media in Crimea, there are only five published in Ukrainian and four in Crimean Tatar. Despite the 250-thousand strong Crimean Tatar population, there is not a single Tatar school. Even though Crimea voted in favour of Ukrainian independence in the 1991 referendum, the early 1990s saw the rise of separatist movements. When the Crimean government introduced the post of President of Crimea, the elected pro-Russian politician Yuriy Meshkov disbanded the Crimean Parliament and called for independence. Separatism flourished as Russia was reluctant to recognise Ukraine’s sovereignty over the peninsula. only the adoption of the Constitution of Ukraine in 1996 and the ratification of the Ukraine-Russia Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership in 1997 (tied to the agreements arranging the status of the Russian Black Sea Fleet until 2017) led to an easing off of territorial tensions. Loyalty to Russia among Crimeans is still strong and this has increased during the last few years. According to a recent study by the Razumkov Centre, a Kyiv-based think-tank, 32 per cent of Crimeans do not consider Ukraine as their native country, while 48 per cent would like to change their citizenship, mostly to Russian. Importantly, 63 per cent of the population would support the idea of Crimea joining Russia.However, there is no single vision on the future of the region – the same proportion would support greater Crimean autonomy within Ukraine. Only 25 per cent are in favour of Ukraine joining the European Union, with 52 per cent against; in Ukraine as a whole, support for EU integration (47 per cent) prevails over opposition to it (35 per cent). Tensions have deepened over land, political, social, economic and language rights, over historic and religious places, and between Kyiv and local authorities. Often the division lines lie between the Russian-Slav and the Crimean Tatar populations. These are exacerbated by the hate speeches of the Crimean media against the Tatars and the Muslim population. Ukrainian authorities have not developed legislation that would renew Crimean Tatar rights as an aboriginal ethnic group. This has pushed the Tatars towards radical behaviour, such as illegal land grabs, street protests and the radicalisation of national movements. Land is one of the major sources of conflict. The land promised to the repatriated Tatars is also a major focus of corruption in which local and national authorities and the Tatar representatives are involved.

INFLUENCE VERSUS GOVERNANCE

When the post-Orange Revolution leadership of Ukraine took a more decisive stance towards EU and NATO integration, Russia, through both its increasingly aggressive rhetoric towards Ukraine and boosted funding for the Russian community of Crimea, signalled that it was willing to use Crimea as a bargaining chip vis-àvis Ukraine. Moscow’s claims toward Crimea have become more frequent, culminating in the Russian State Duma’s decision to seek the abrogation of the 1997 Treaty if Ukraine joined the Membership Action Plan for NATO or forced NATO accession. Additionally, the Russian media have created an image of Ukraine as a country that discriminates against the Russian-speaking population.

The Russian position is backed by the influence it has over the Crimean peninsula, which is stronger than that of Ukraine. A constant source of tension in Ukraine-Russia relations, the Russian Black Sea fleet is also a main source of income for the Sevastopol budget and inhabitants. Russia is the largest investor in the region and the main destination of Crimean exports – although overall Crimean exports to the EU almost equal those to Russia. The dominance of the Russian media and the power of pro-Russian political parties is crucial. The Russian Community of Crimea (RCC), an NGO funded by the Moscow major Yuriy Luzhkov’s “Moscow – Crimea” Foundation, together with the Russian Block, has a 30 per cent quota in the Block for Yanukovych, which has formed an 80-seat ruling coalition together with other pro-Russian parties in the 100-seat Crimean Parliament. Moreover, the RCC’s head, who holds the chair of the Crimean parliament’s deputy speaker, is a member of the Compatriots’ Councils for the Moscow government and the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Although Crimea is an issue in Ukraine, Kyiv has no Crimea policy. As some European diplomats cautiously note, the political establishment in Kyiv cannot – and perhaps does not want to – make serious efforts to integrate Crimea fully into Ukraine’s political and social context. Rather, it is merely interested in keeping the current status quo. Indeed, Kyiv lacks the necessary resources, and the political elite remains inward looking. The national government fails to implement even the adopted policy decisions regarding Crimea. Local Crimean authorities feel unheard and ignored by the Kyiv government as political dialogue is limited to the party structures’ communications during the electoral campaigns. No wonder there is often harsh Crimean resistance following decisions by Kyiv, as happened after the decision of the Minister of Education to introduce school graduation tests only in Ukrainian. In critical situations the Crimean politicians and population reveal more public support for the Russian authorities than those of Ukraine.

Despite the favorite local habit of waving Russian flags (although the Crimean, very similar to the Russian, is much more popular) and protesting on every possible occasion against NATO, most experts agree that there is a reasonably strong Crimean identity among locals – Russians and Tatars both. Moreover, Crimean politicians certainly feel that the depth of the autonomy ensured by the weakness of the Ukrainian government gives them a stronger position than the authoritative Russia ever would.

Last, but not least, Kyiv tends to forget its biggest leverage toward Crimea – its European integration plans. With more Western (especially European) engagement, Crimea could even be an engine of integration, as socio-economically it would probably benefit the more from this than other regions. This dimension could in fact capitalise on the growing interest in Crimea’s development expressed by the EU.

THE EU AS NEWCOMER

By facilitating social and economic development, promoting good governance, access to citizens’ rights and democratic dialogue, and increasing the demand for European integration, the EU would help avert the roots of internal conflicts. Despite the geopolitically oriented rhetoric, local partners nurturing the status quo are ready to cooperate, especially as the EU is a more credible partner for Crimea’s society and authorities in contrast with the U.S. This would be the EU’s long term investment not only in projecting stability in Crimea, but in the whole Eastern Neighbourhood.

Within the political dialogue with Ukraine, the EU should press the Kyiv government to continue with decentralisation and local and regional government reforms, focusing on economic development (based on the wasted potential of Crimea in trade, tourism, etc.), as well as introducing effective multi-ethnic management that might encompass all the key ethnic groups living in Ukraine today.

At the regional level, apart from the economic and social development of Crimea, the EU should aim at promoting socialisation and better communication in a Crimea-Ukraine-EU triangle through the following policies: educational mobility both to the EU and within Ukraine of Crimean students and teaching staff; joint EUCrimea university programmes in such areas as tourism; mobility programmes for journalists

and local government representatives; European-Crimean twin towns programmes; and trilateral (EU-Ukraine-Crimea) and bilateral (EUCrimea, Ukraine-Crimea) civil society cooperation in areas of human rights, good governance, multicultural and multi-ethnic management and community services.

European-Crimean cultural communications should be facilitated. EU member states’ institutions should launch their activities in Crimea. People-to-people contacts would benefit from the development of low-cost international air and sea transport communications. The EU countries’ consular networks should be spread to Crimea to support trade, cultural activities, people-to-people contacts and a better understanding of the region. None of the EU member states has its consulate in Crimea. Lithuania, Estonia and Hungary have honorary consulates, while the closest consulates are those of Poland, Romania, Greece and Bulgaria, in Odessa. Internationally, the EU should make better use of the opportunities for regional cooperation opened up by the Black Sea Synergy and the Eastern Partnership and seek for the promotion of EU-Ukraine-Russia and EU-Ukraine-Russia-Turkey cooperation aimed at the development and European integration of Crimea.

За матеріалами NGO "Fride"