When

the European parliament issued a critical report on Egypt's human rights record

in 2008, the Mubarak regime responded with nationalistic fury. The Muslim

Brotherhood, on the other hand, sided with Europe.

"Respect of human rights is now a concern for all peoples," its

parliamentary spokesman, Hussein Ibrahim, declared at the time.

That

Islamist movements, or at least the more mainstream ones, should take an

interest in human rights is not especially surprising. They have, after all,

experienced repression at first hand and had years to reflect upon it. There

are some obvious limits, though. While

acknowledging universal rights up to a point, they still hanker after cultural

relativism. Ibrahim for his part added an important rider, that "each country has its

own particulars" -- and made very clear that in Egypt's case the

Brotherhood excludes gay rights.

It's

a similar story in Tunisia now where the moderately Islamist

Ennahda party

dominates the post-revolution government. Samir Dilou, the country's first

human rights minister (and a member of

Ennahda) caused an outcry from activists

last month by

saying

on television that sexual orientation is not a human right and described

homosexuality as a perversion requiring medical treatment. Amnesty

International quickly sought to disabuse him,

pointing

out in a letter that "homosexuality stopped being seen as an illness

or a "perversion" by world medical organizations and associations decades

ago."

Dilou's

remarks, though, confused and homophobic as they might seem, also suggest that

Islamists -- some of them at least -- are beginning to shift their ground. He

didn't, for example, invoke religious scripture to denounce homosexuality as

one of the most heinous sins known to man or suggest that gay people should be

put to death, as many Islamic scholars have previously done. "We are not

inciting anybody against homosexuals," his press secretary

said

later, but "Tunisia's distinctiveness as an Arab-Muslim society must

be respected."

Unintentionally,

perhaps, Dilou's remarks also raised a tricky question for Tunisia's

"distinctive" society. If homosexuality is now to be regarded as an

illness rather than a sin, how can they justify continuing to criminalize it,

with punishments of up to three years in jail for offenders?

The

"sickness versus sin" debate is a familiar if futile one, but

sometimes a necessary step in adjusting to reality -- an attempt to find some

middle ground between moralistic rejection of homosexuality and acceptance. To

those who can't accept gay people the way they are, the idea of

"curing" them can seem more enlightened than punishing them, and some

societies have hovered for a time between the two. Britain in the 1950s, for

instance, provided "treatment" for gay men (sometimes even in the

form of chemical castration) as an accompaniment, or sometimes an alternative,

to prison.

Arab

societies today are in a similar position. Discovering a gay son or daughter in

their midst, some families react punitively and throw them out of the house.

Others send them to psychiatrists. Which they choose is partly a matter of

class and partly a matter of how "traditional" or "modern"

the family consider themselves to be.

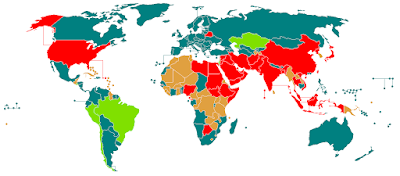

Same-sex

acts are illegal in most Arab countries, and even in those where they are not other

laws can be used -- such as the law against "habitual debauchery" in

Egypt. With a few exceptions, though, the authorities do not actively seek out

people to prosecute. The cases that come to court often do so by accident or

for unrelated reasons. This is mainly a result of denial: large numbers of

prosecutions are to be avoided since that would cast doubt on the common official line

that "we don't have gay people here."

To

continue denying that gay Arabs exist, though, is increasingly difficult.

Thanks to the internet, young Arabs who experience same-sex attractions can now

find information that helps to explain their feelings and gives them a sense of

identity, as well as providing the means to contact others of a similar

disposition. Gay

activism in Arab countries is still on a relatively small scale, but it is growing.

The Lebanese LGBT organization,

Helem, has been functioning openly in Beirut

for almost 10 years now and has won some recognition from the government for

its work on sexual health. There are numerous gay Arab blogs and websites, and

the latest addition in Tunisia is a

magazine called "Gayday".

Inevitably,

this draws a response from those who are fearful of change -- sometimes a

violent one. In post-Saddam Iraq, men suspected of being gay, or simply not

"masculine" enough,

have been killed by vigilante squads

and the number probably runs into the hundreds. The authorities turn a blind

eye while newspapers provide incitement with articles condemning

"fashionable" (i.e. western) hairstyles and clothes. Many

Arabs blame the West for spreading homosexuality and other forms of

"immorality" but also look to the West for solutions. A series of

articles at IslamOnline (an Egyptian-based website supervised from Qatar by the

famous cleric, Youssef al-Qaradawi) provided what was claimed to be a

scientific look at homosexuality, based on the idea that sexual orientation is

a choice which can also be "corrected". Its main source for this was

not Islamic teaching but the

National Association for Research and Therapy of

Homosexuality (NARTH), a fringe psychiatric organization in the United

States which promotes "sexual reorientation therapy."

Such

arguments may offer a rationale for not punishing homosexuality but they cannot

offer a genuine way forward. The arguments themselves are already thoroughly

discredited and adopting them is nothing more than an avoidance mechanism,

postponing the day when fundamental questions will have to be addressed.

The

core of the Arab Spring is a revolt against authoritarian rule, but to bring

real change the struggle cannot be limited to merely overthrowing regimes; it

also has to tackle authoritarianism in society more widely. Doing that is more

about changing attitudes and ways of thinking than politics: even as dictators

fall, the Mubaraks of the mind are yet to be confronted. Attitudes towards gay rights are therefore an

important measure of how far, or not, a society has moved from

authoritarianism. Gay rights in the Middle East are not simply about gay

people; they are intimately bound up with questions of personal liberty, the

proper role of governments, and the influence of religion. Demands for gay

rights add to the broader pressure for change and, conversely, progress in

these other areas can ease the path towards gay rights.

Criminalization

of homosexuality, for example, reflects abhorrence of the act but also a

philosophy of government that seeks to regulate people's behavior in matters

that ought to be no concern of the state. This applies at many levels, not just

sex -- from the imposition of dress codes in some countries to the notion that

publishing a newspaper or establishing an NGO requires permission from the

government.

As

far as religious attitudes to homosexuality are concerned, the debates in Islam

are very similar to those in Christianity and largely boil down to a question

of how believers interpret the scripture. So far, Muslims have generally been

more resistant than Christians to admitting the possibility of new scriptural

interpretations. One reason is that the "doors of ijtihad" (independent interpretation rather than dogmatic acceptance

of established views) have long been considered closed. Another is insistence

on ahistorical readings of the Qur'an -- the idea that its injunctions are valid

for all times and all places and cannot be modified in the light of changing

times and circumstances.

To

successfully make an Islamic case for gay rights, those barriers have to be

broken. Again, though, the key point is not homosexuality itself but the

underlying principle: a more open and questioning approach to religious

teaching unblocks the road to many other things.

While

the calls for freedom heard during the first year of the Arab Spring have been

mainly directed against unaccountable governments -- a demand, in a sense, for

collective liberty -- there is also an undercurrent seeking liberty at a more

personal level. This is a fundamental issue but one that Arab societies are

reluctant to recognize because of the value placed on pretensions of unity

(national, cultural, and religious) and conformity with social norms.

The

rights of minorities are rarely considered seriously and, if they are discussed

in public at all, it's usually to emphasize how harmoniously everyone is

getting along. When conflicts break out -- as between Christians and Muslims in

Egypt -- they are quickly hushed up rather than being examined and addressed. At

the root of this is an aversion to fitna

or social strife -- a feeling that difference is a problem and a source of

embarrassment. The idea that diversity has some intrinsic value, and that it

can enrich a society if handled properly, has not yet taken hold. Overcoming

that is one of the main challenges for ethnic and religious minorities, along

with those who are outsiders for sexual or other reasons.

Another

huge challenge for the future is entrenched and continued patriarchy. Arab

leaders personify it, but it is imbued throughout society and built on

rigidly-defined gender roles in which traditional concepts of

"manliness" are highly prized. Intentionally or not, gay people

undermine that simply by asserting their presence -- as do women.

In

the meantime, of course, Arabs are preoccupied with more broadly rendered and

elemental struggles in Syria and elsewhere. But in this the question of gay

rights cannot be set aside indefinitely. At some point it will have to be recognized

as a part of the process of change, and inseparable from it.